The Three Pillars of Value-Based Pricing

Maximize the return on your self-storage property with time-tested strategies.

Introduction

Profitable pricing starts with understanding the value you deliver to your customers and matching the right price to this value in every sales transaction. The most effective way to accomplish this is through Value-Based Pricing (VBP), which provides optimal results when combined with efficient value-selling strategies based on behavioral economics and psychology.

Value-based pricing is one of the most commonly misunderstood concepts in the self-storage industry. At the core of VBP is the differentiation between the products you are selling.

For differentiation to be effective, your products need to be sufficiently different so that customers can easily perceive the value difference between any two products. Your viewpoint or your perception of customer value is unimportant in this context. What is important is how your customer perceives the benefit of one product over another. In other words, you need to justify the price difference relative to the value disparity the customer perceives.

In this blog, we explain that an effective value-based pricing strategy must have three pillars:

- Segmentation or differentiation based on the different products you offer.

- Data-driven algorithms to help determine the optimum prices.

- The value-selling process with tactics based on behavioral economy and psychology.

Together, these three VBP pillars help you achieve impressive sales conversion rates at higher prices.

Pillar 1 – Segmentation

Segmentation is the process of classifying customers into various small groups which have similar or related preferences or desires. Identifying pricing segments that guide effective sales decision-making and marketing is one of the most critical benefits of any Revenue Management (RM) system.

Self-storage operators, however, know little about their new customers (although this might change with better data collection in the future). As a result, operators mainly use unit types as a proxy to segment their customers; that is, they utilize product segmentation.

For product segmentation to work effectively, unit types (i.e., pricing segments) must be differentiated so that segments differ significantly from one to another in the eyes of the customers. What differentiates the units in the eyes of a customer? Is it size, convenience, climate control, 24-hour access, security cameras, or other factors?

Value-based segmentation explores these “value drivers.” It classifies units with the optimum level of granularity so that prices are logically positioned with respect to each other based on the implied value or customer expectations of value. For example, all other factors being equal, customers value:

- larger units more than smaller units

- climate-controlled units more than non-climate-controlled units

- drive up units more than the interior units

- ground floor units more than upper or lower floor units

- units with elevator access more than units with stair access

- units closer to the entrance more than units that require significant navigation in the hallway

- covered parking more than uncovered parking

Value-based segmentation ensures that customers are paying revenue-maximizing prices for each unit type. For example, charging the same price for climate control and non-climate control units risks undercharging climate-control customers, causing foregone revenue, and overcharging non-climate control customers, leading to additional foregone revenue since customers could rent from other operators.

Segmentation might generate hundreds of potential unit types based on the combinations of the possible value drivers. Yet, it is essential not to go overboard and create too many unit types (or pricing segments). It is unnecessary to differentiate every size, feature, or location, as minor differences among units will have little impact on perceived value and instead create unjustified complexity. You do not want to end up simultaneously charging different prices for identical units next to each other, as communicating the benefits of one over another is impractical and would lead to a negative customer buying experience.

The goal is to create a win-win for operators and customers so that everyone feels like they get something based on the level of differentiation among unit types. After all, no exchange takes place unless both parties obtain a benefit.

Pillar 2 – Price Optimization

Once we understand the segmentation of unit types, the next step is to optimize the relationship between the value of each unit and its price. This step is about understanding how customers behave in the real world and, with the help of lots of data, analyzing this information to optimize the price.

In this step, we use sophisticated customer choice and optimization models to quantify the worth of each unit type. We analyze readily available data, such as inquiries, reservations, move-ins, street rates, incentives, occupancy levels, vacant days, in-place rents, and competitive rents. We also consider various derived factors that influence the price of a unit, including conversions, move-in and move-out forecasts, supply availability, competitive prices, price sensitivity estimates, promotions, and statistical rent bounds. This can only be done with sophisticated optimization algorithms.

The exact nature of these price optimization models and calculations depends very much on the availability and quality of data. Still, the objective is the same – finding the optimized rents customers are willing to pay for each store and unit type.

Pillar 3 – Selling Value

With the optimum prices at hand, now the question is how to value-sell the units, online and in-store so that you increase the customers’ perceived values and get more move-ins with higher prices. This involves communicating value and leveraging psychological factors influencing customer buying decisions.

Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize for Economics winner, argues that humans seldom select things in absolute terms. We do not have an internal value meter that tells us what things are worth. Instead, we can evaluate based on the relative advantage of one thing over another and estimate the value accordingly. For example, we may not know how much a 10X10 Ground Floor unit is worth, but we can assume that all other factors being equal, it is more expensive than a 10X10 Second Floor unit.

Kahneman also argues that we have a powerful anchoring bias, a form of cognitive bias that causes us to focus on the first available piece of information (“the anchor”) when making decisions. For example, in the context of pricing, companies will show an initial price for a product but point out that it is now being sold at a discount. Companies also display a highly-priced product next to a regularly priced one to make the second product look inexpensive.

These insights teach us four value-selling tactics for self-storage units:

i. Never present a unit type by itself

Regardless of how economical the unit is, we do not know if we are getting a good deal when we see a unit alone unless we are anchored to a list price or we have seen the price of a similar unit elsewhere.

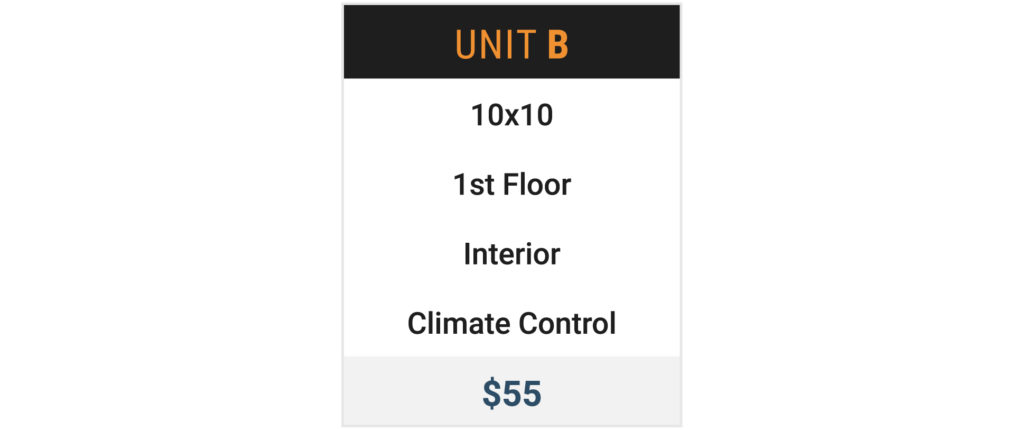

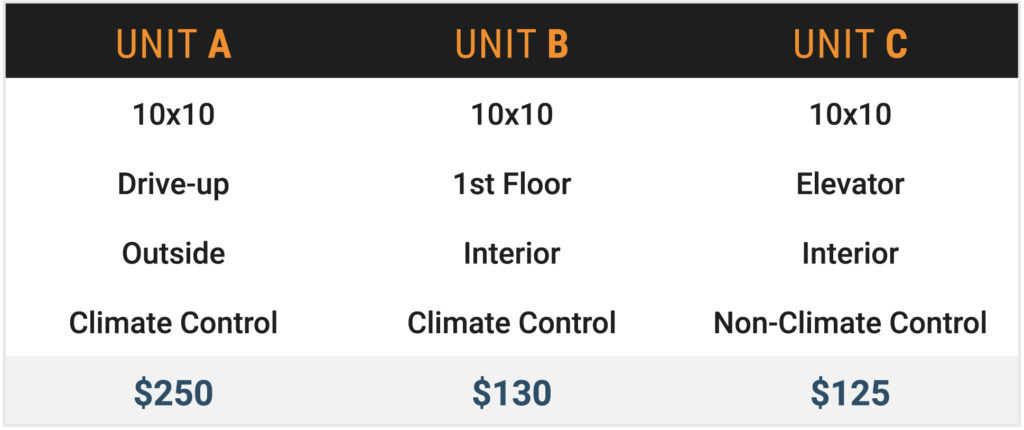

Some operators show the most affordable unit by itself to drive traffic to their website. Yet, it is better to provide a frame of reference for helping them establish value for your product. If we see it alone, we do not know if $55 is a reasonable price for Unit B.

ii. Always anchor to a price

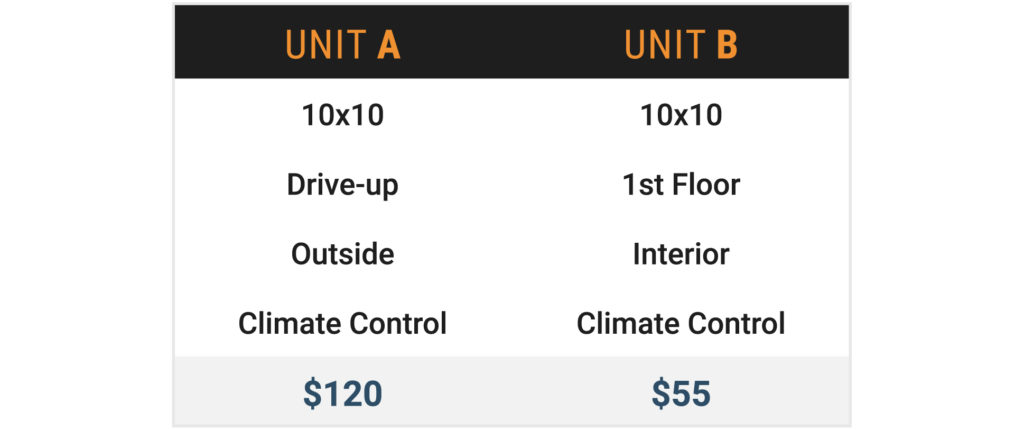

One way to establish value is to show a discount with “$110 $55”, where $110 is the anchor price for the $55 price. A more effective way is to show Unit B and Unit A next to each other. This display would make Unit B look like a bargain since the price of Unit A is disproportionally higher.

It is essential to present the highly-priced Unit A first since Unit B will look much cheaper in comparison. For the example above, the operator has a limited number of Unit A and high availability of Unit B (perhaps with competitors). The display will stimulate sales of Unit B due to the big price difference. In this case, Unit A is used as an anchor to Unit B. Needless to say, it would also be a win if Unit A is purchased by price-insensitive customers who value outside drive-up units.

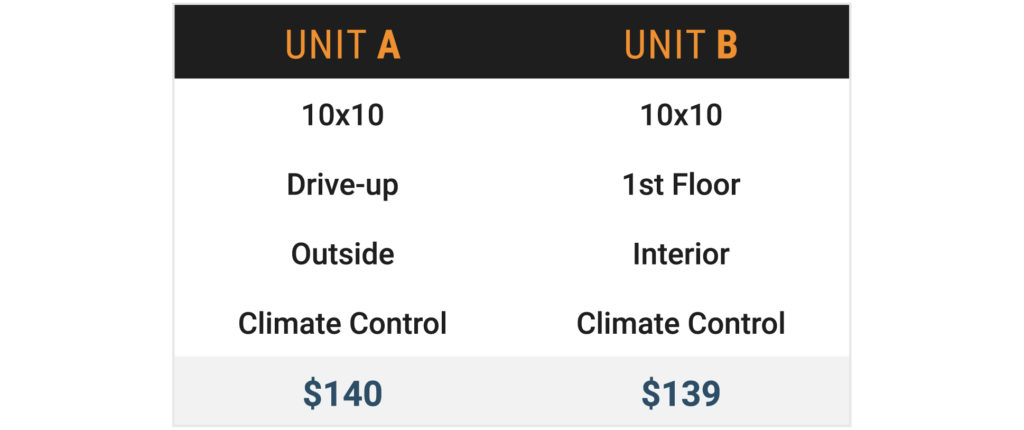

You can also anchor a unit to a lower price, as per below. Unit A would be a more attractive option in this situation due to its attributes. Here, the operator creates an effective sales tactic to sell the outside drive-up units with high availability by anchoring to the first-floor interior unit with low availability.

iii. Show comparable unit types with clear differences that matter to customers

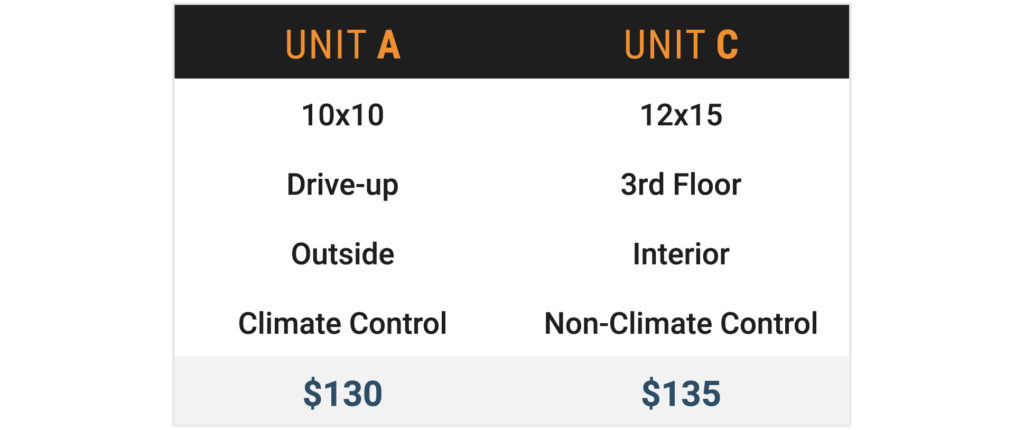

When showing comparable or similar units next to each other, ensure the more expensive unit has a clear and differentiated attribute. For example, comparing Unit A and Unit B in the above tables is simple.

However, it is not easy to decide between Unit A and Unit C in the table below as they are entirely different products. Customers must do a lot of thinking (and you do not want that) to see which deal is better, and this is likely to cause indecision.

iv. Do not show or display more than three unit types

You should at most show three comparable unit types and price them based on which one you want to make it more attractive. The easiest way to do this is by displaying similar units with anchor prices from above and below. Showing many different options creates a choice overload and leads to what is referred to as “cognitive impairment,” in which people would have difficulty making decisions when facing many alternatives.

For example, it is effortless to understand the unit types and compare the values of the three options below. First, they have the same size and are classified as Unit A, Unit B, and Unit C based on their features and locations. Pricing is also displayed next to each other, leading to easy decision-making. We recommend that customers are guided first to select the possible size group they need (E.g., Extra Small, Small, Medium, Large, Extra Large ) before showing options Unit A, Unit B, and Unit C. In this case, most customers would choose Unit B since it is anchored to a very high price from above and a low price from below with a significantly inferior unit.

The most critical factor affecting customer choice and willingness to pay is the alternative units under consideration for purchase. Value-selling on the web requires us to understand this fact and use these tactics. They have been proven to work well in many settings by behavioral economists and psychologists, and they are likely to have an impressive effect on your purchase conversions.

In the store, the selling process could start by asking prospects open-ended questions about their needs and funneling them down to understand the size, feature, and convenience they would value most (keep the price out of the initial discussion if possible). The salesperson could then show the most expensive unit that matches the customer’s preferences. If the price of that unit is less than or equal to what the customer is willing to pay, then you will likely close the sale. Otherwise, show a less expensive unit with less desirable features and location and justify the price differentials based on their differences. Showing an inexpensive unit after an expensive unit will make it look cheaper than it is and increase the purchase probability.

Conclusions

For value-based pricing to be successful, it needs to combine three core elements. Together, these work to maximize revenue growth and create a better customer buying experience. Segmentation, foundational for VBP, often causes some confusion but is a relatively straightforward concept. The key to remember is that if you over-segment your units, you cannot create the right differentiation, price them optimally, and sell on value. Conversely, if you under-segment your units, you will underprice some units and overprice others.

Perhaps the most complex element of value-based pricing is price optimization through data-driven insights and advanced algorithms. These algorithms help you determine the optimum price in real-world market conditions, considering your customers, competitors, seasonality, occupancy rates, and many other factors. Fortunately, pricing science is rapidly advancing and can help self-storage operators determine the optimum prices under multiple market conditions. Knowing the optimum price for your units helps with your VBP strategy. Without it, you cannot sell on value as you will not correctly know which units to promote, which units to anchor to, and which units to maximize yield.

The final element of an effective value-based pricing strategy is something that savvy businesspeople have long since discovered. You must anchor to a price, show similar products for value comparison, and avoid confusing customers. If you do not use these value-selling tactics, you will be unable to maximize your revenue potential, even if you have the right segments and optimized prices.

Effective value-based pricing strategy is within reach for all self-storage operators – large and small – and something that operators cannot afford to overlook.